|

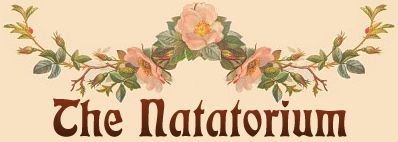

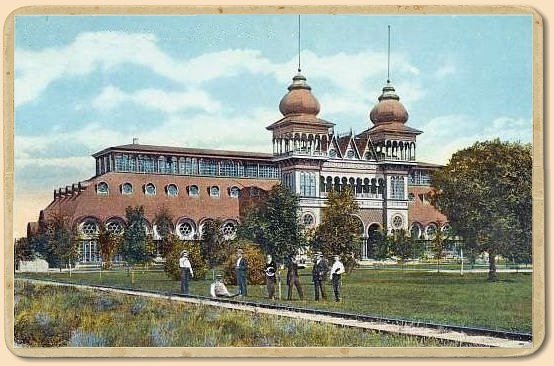

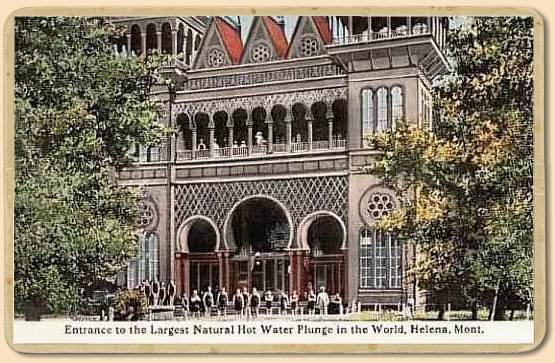

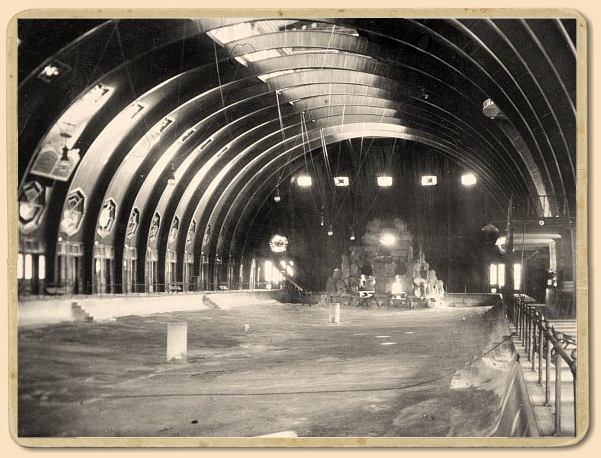

The spectacular natatorium was designed

by the German-born Helena architect

John C. Paulsen, and his partner Noah J. McConnell.

View

looking northeast, ca. 1908

LIBRARY

OF CONGRESS

| The

natatorium was the most important example of Moorish architecture

in the Northwest. It housed the largest indoor "plunge"

in the world. A rectangular nave covered the 300' x 100'

pool. The

hot-spring water for the complex was delivered via redwood

pipes from the source 1.5 miles to the west. Over one million

gallons per day of hot and cold mountain spring water flowed

through the system. The pool had

a maximum depth of 12'. |

|

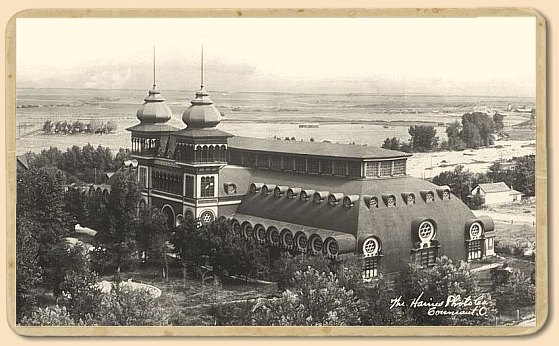

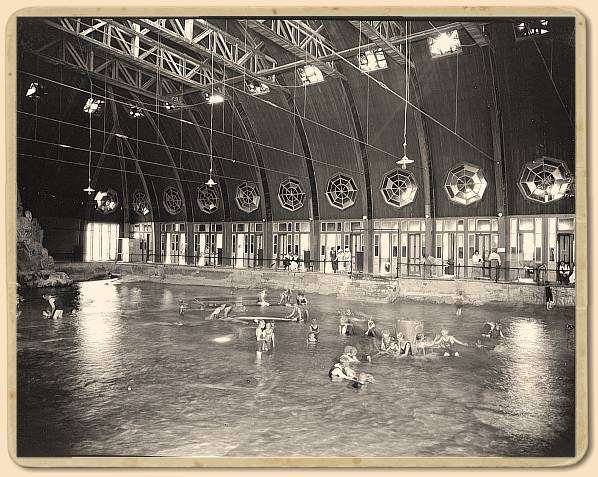

An

unusual early view, showing the eastern side of the natatorium.

Beneath

the lower circular windows was a long row of dressing

rooms. On the hillside in the foreground, note the upper

(1865) and lower (1873) "Yaw Yaw" ditches, carrying

water from Ten Mile Creek to Helena.

|

DETAILED

VIEW

PRIVATE COLLECTION

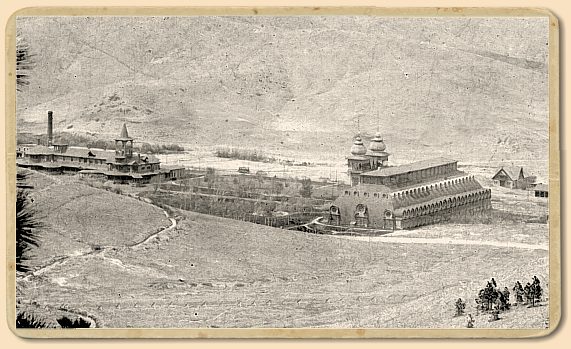

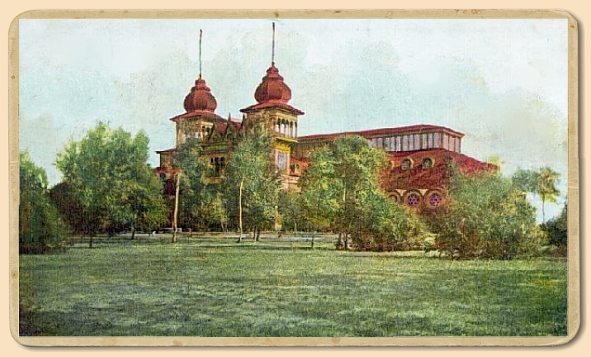

Natatorium

and Mount Helena, looking southeast.

|

MYSTERIOUS

DEATH AND BURIAL OF THE ARCHITECT

|

|

The

architect of the natatorium, John C. Paulsen, had a history

of political corruption relating to the construction

of public projects. In 1896, seven years after completion

of the Broadwater project, he became embroiled -- as State

Architect -- in a major kickback scandal involving construction

of the Montana

Capitol Building.

On March

31 1897, just hours before he was

to testify before a Grand Jury, Paulsen's wife found

him dead in the bathroom of his Kenwood home. The coroner's

official finding was that Paulsen died of a stroke

("cerebral apoplexy"), but other persistent

reports claimed he died from a gunshot to the head, perhaps

self-inflicted -- perhaps not.

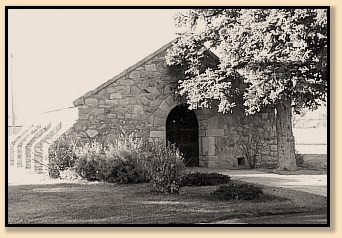

RECEIVING VAULT - FORESTVALE CEMETERY

PHOTO BY RIC SEABROOK, COURTESY OF CHARLEEN SPALDING

Because

the ground was frozen and burial impossible, his body

was placed in the Receiving Vault at Helena's Forestvale

Cemetery to await the thaw; but the suspicious circumstances

surrounding his death - and claims that he had been sighted

alive and well - necessitated an identification of his

body shortly after his death, mainly for insurance purposes.

Records

of the Herrmann & Co. Funeral Home in Helena state

that on May 6 1897, they dispatched a driver and wagon

to Forestvale to carry Paulsen's zinc-lined coffin to

the railroad depot for transport to an unnamed location.

There, John C. Paulsen slipped from history; there is

no record known of the final dispostion of his remains.

Reports

that Paulsen committed suicide continued into the

20th Century; the newspaper clipping below is from the

March 30, 1902 Atlanta Constitution...

Will

we ever know the real story? It's

doubtful. When corrupt politicians and large sums of money

are involved, the truth is naturally scarce -- and people

are quite expendable.

•

MANY THANKS TO HELENA HISTORIAN CHARLEEN SPALDING FOR

HER HELP WITH THIS SECTION •

|

Natatorium

from the NW. Patrons

waiting for the trolley.

Natatorium from the SW.

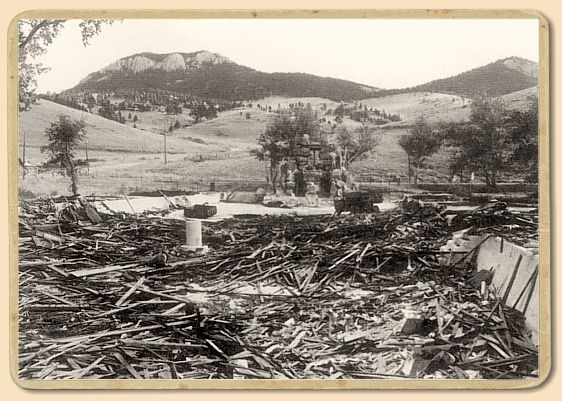

| At

the southern end of the pool, there arose a 40' high waterfall

made

of huge granite boulders. It stood alone and open to the

elements for decades after the plunge was demolished. |

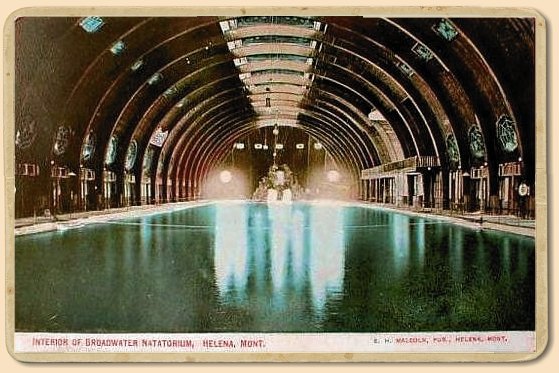

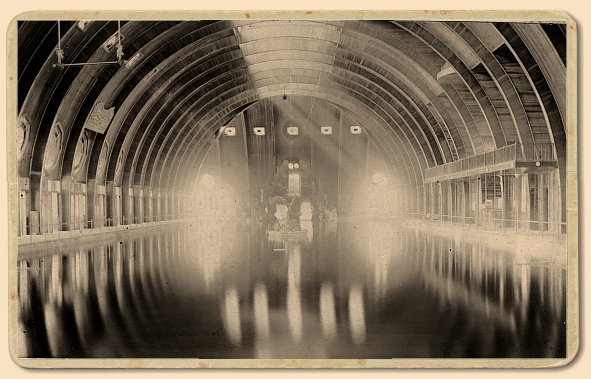

An

early interior view by photographer Arthur Canning.

COURTESY

OF SCOTT NELSON - THE

BRIDGEWORKS CONSERVANCY

|

There

were "toboggan planks", springboards, and an

observation gallery.

Stained-glass windows and clestories ringed the pool,

and rows of high windows admitted light to the interior.

Colorful tiles covered the floors and walls. There were

100 steam-heated dressing rooms. When the electrically-lit

natatorium was viewed from outside at night, it was said

to glitter like a box of jewels.

|

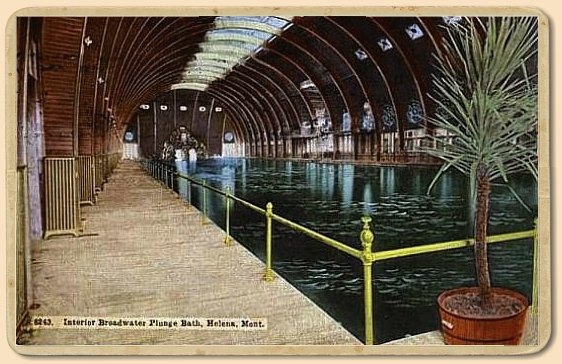

COURTESY

OF SCOTT NELSON - THE

BRIDGEWORKS CONSERVANCY

|

Natatorium

interior, 1940. Note the roof trusses which were

added to stabilize the structure after the 1935

earthquakes. Although unattractive, the trusses

did their job. The insurmountable problem caused by

the earthquakes was the collapse of the thermal vent

which provided hot spring water for the pool. Attempts

were made to keep the pool filled by transferring hot

water from the hotel boilers. Then, they simply tried

to get by with using less water, as sen in the photo

above. But it was all to no avail, and the natatorium

was finally closed.

The Broadwater acreage was

purchased by Norman Rogers in November of 1945.

He announced plans to renovate and reopen the resort,

but this was never done. In July of 1946, Rogers threaded

thick steel cables through the windows of the natatorium,

hooked them to a bulldozer, and began pulling down the

historic structure. "She's still stubborn",

Rogers was quoted as saying as the great building shuddered.

There were rumors that the timbers and cedar paneling

were then sold for firewood.

As

late as 1948, Rogers claimed he intended to renovate

and reopen the resort, but what was left of it continued

to decay. For decades, the stones of the waterfall stood

as the only visible reminder of the opulent plunge.

Now they too are gone.

|

Demolition

of the natatorium, 1946.

MONTANA

HISTORICAL SOCIETY

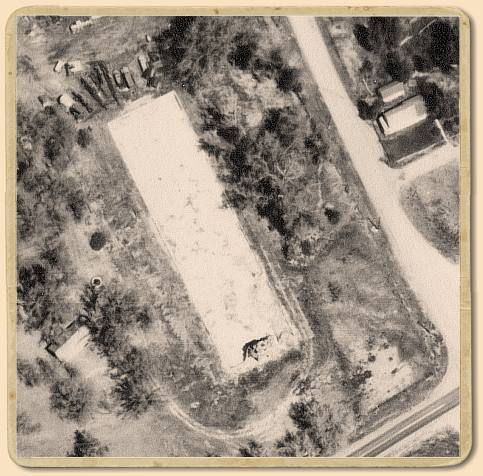

Aerial

view of the open pool, 1953.

COURTESY

OF SCOTT NELSON - THE

BRIDGEWORKS CONSERVANCY

Recent

satellite view of the Natatorium site.

|